I will continue teasing my upcoming Crisis on Infinite Earths (COIE) article (part of my Event Horizon column) by dropping another interesting bit of comics history that had to be mostly left on the cutting room floor. Here’s the story of Omniverse magazine, a 70s fanzine founded by Mark Gruenwald. Gruenwald, for those who don’t know, was a Marvel editor and writer best remembered for creating the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe (1982), his long run on Captain America (1985 to 1995), the Squadron Supreme mini-series (Sep 1985 – Aug 1986), and Quasar (1989–1994). But, what many don’t know, is Gruenwald’s interest in fictional continuity — especially in the Marvel and DC superhero universes — indeed he can be considered one of the foremost theoreticians of the concept. The story of Omniverse magazine is largely also Mark Gruenwald’s story.

A Universe Emerges

By the mid ’70s, a new generation of authors and cartoonists entered the comics bullpens. They had grown up reading superheroes. As fans, they brought with them a new level of understanding of the superhero universe. They understood the value of the comic book crossover as fans, as readers, and now as writers. What was once valuable in terms of sales (crossovers often produced temporary sales bumps, especially when lower selling titles featured a popular character as guests), now became valuable on a narrative and mythological level. To this new generation, the value did not reside in each character, it resided in the world of characters. Crossovers became more frequent and created valuable narrative connections between comics and characters. Fans were encouraged to read more titles, as not to miss out on what happened in other corners of the universe. The story they were reading in Fantastic Four might have origins in another one in The Avengers. Heroes and villains could help each other out in different books. A shared narrative universe emerged out of a series of loosely related titles.

The Journal of Fictional Reality

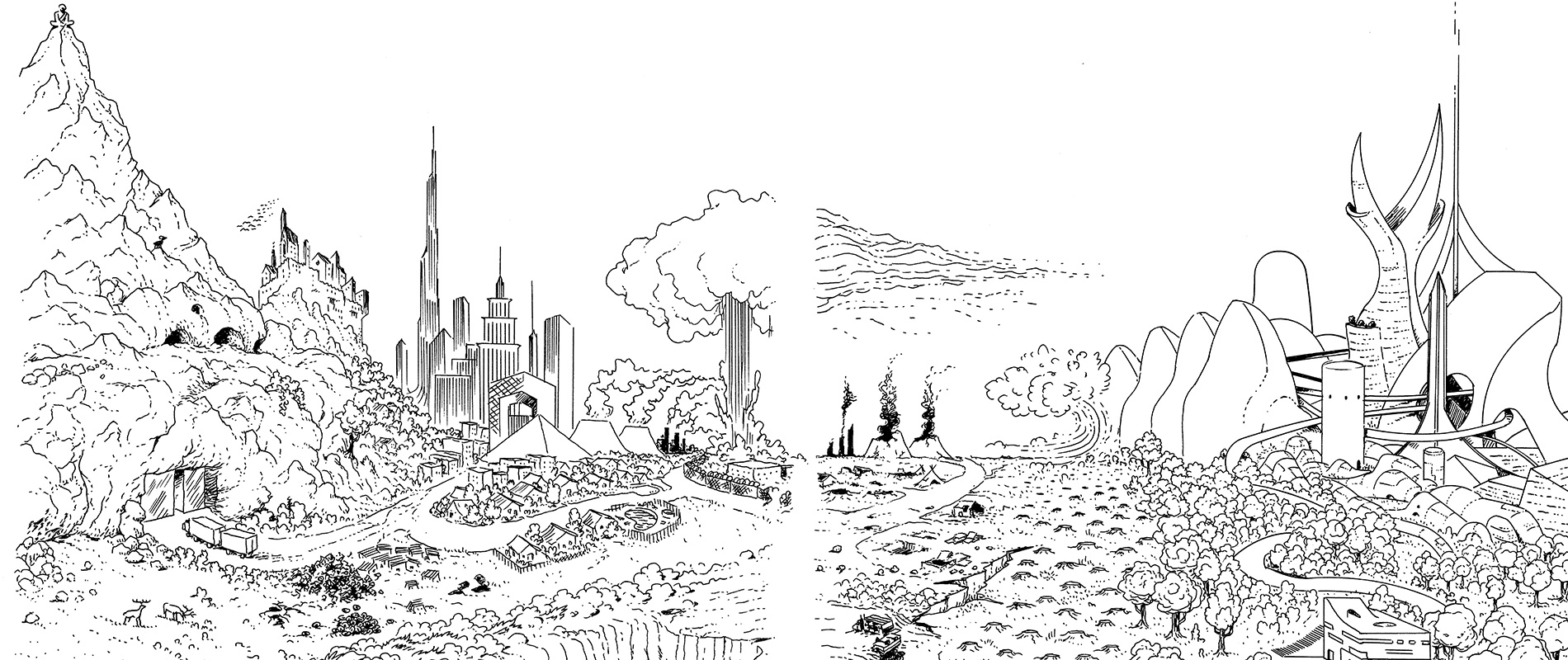

The Fan press understood this as well. One of the most interesting fan publications of that era is Omniverse: The Journal of Fictional Reality, edited by Mark Gruenwald. The first issue, from fall 1977, is a masterpiece of theoretical world building. In the editorial, Gruenwald lays out the case for reading Marvel and DC comics as coherent universes. The entire magazine is devoted to explicating, explaining, and justifying the connections between the various inconsistent realities of the Marvel & DC universes. It’s grueling metaphysics, building the ontological maps for the weird-reality of the two universes. The seeds of the massive crossovers of the Event were sown here. Even some of the graphics prefigure the visual identity of COIE.

Gruenwald defines “omniverse” as “the continuum of all universes, the space/time matrix that comprises all alternative realms of reality.” He also does not limit the omniverse to only comics, “In times to come, we hope to broaden our scope and place all forms of fiction under scrutiny. Til then, OMNIVERSE, will emphasize comic books over non-pictoral prose, due to the editors’ background in comicology.”

Reality Rating

One of the more fascinating items in Omniverse is its review column. Most fan press reviewed comics based on the quality of art or writing, but Omniverse had to be different. Its review column, “Case Studies” (Omniverse #1, p.19-23), rates comics on their ‘Reality Rating’. The Reality Rating rates comics based on their overall depiction of reality. The ratings go from A to D:

- Enhances continuity or illuminates some new facet of reality.

- Despite some minor oversights, solid in its depiction of reality.

- Major problems in its depiction of reality, but still explainable.

- Detrimental to the reader’s understanding of reality.

The ratings are not concerned with how well the comics conform to OUR reality (the one we live in), but how well they conform to the fictional reality they are part of. Special praise is heaped on comics that expand the scope of that fictional reality. For example, What If #3 gets an ‘A’ “by virtue of its tighter terminology about parallel dimensions.” (Omniverse #1, p. 23). On the other hand, Thor Annual 5 gets a ‘C’ because it introduces an inconsistency with the Norse & Olympian Gods within the Marvel Universe. The story depicts the gods as needing the ‘belief of mortal men’ (p. 20) to exist, when in fact they have been previously depicted as independent other-dimensional beings without the need for ‘belief’ to sustain them.

The Reality of Reality

For much of their existence, comics stories for the most part existed in a kind of ‘situational comedy’ vacuum. Sure, there was some continuity, but for the most part, when an adventure ended, the world ‘reset’. The consequences of previous issues rarely had an impact on subsequent issues. Often, they introduced contradictions instead. For example, it might be written by someone less familiar with that particular character’s mythos, or simply because it was an interesting use of the character. Tight continuity, or consistent history of the character (the one exception being the origin story), had no value for a long time. The idea of a major character dying, and remain dead, for example, was still shocking at the time. It was a frequent trope to kill a character, only to resurrect them again later via some implausible deus-ex-machina plot device.

But once creators take continuity and ‘reality’ of the fictional world seriously, it’s a short distance to say, Watchmen (which imagines what our ‘real’ world would be like once you add superheroes, with all the dark subtext and unintended consequences laid bare). Much of the innovation in comics of the 80s was simply creators taking fictional words seriously (however absurd they may be) and telling the stories that resulted from that seriousness.

Seeds of Crisis

Reading Omniverse, there’s a palpable sense of the theoretical case that Wolfman made for COIE. Omniverse is perhaps the most sophisticated explication of the various narrative complexities of the DC and Marvel universes. If this is what ended up in print, one can imagine the various theoretical constructions that circulated among the fandom in the years prior.

When writing about COIE, many of the concerns cited by Marv Wolfman as ‘problems to be solved’ in DCU continuity (multiple versions Atlantis, inconsistent futures, multiple Earths), are already present and explicated in Omniverse. For example:

- The various manifestations of Atlantis are discussed, and possible explanations for the inconsistencies are explored.

- The inconsistent future(s) inside of the DCU are enumerated. For example, Kamandi’s nightmarish apocalyptic future does not match up with Legion of Superheroes’ bright technological near-utopia of the 30th Century.

- There is a lengthy explication of the various multiversal, interdimensional, and time travels of The Flash. Many of these stories were key to COIE.

Omniverse shows these ideas and concerns were already advanced and present in the fandom, and among the writers who would eventually be given keys to the DC and Marvel universes.

Crisis Identity

Another eerie premonition of COIE is visual. It is the graphic for the Flash article (“Reality Spotlight on The Flash” p. 24-28, art credited to Dennis Jensen, whose work I’ve never encountered elsewhere). The graphic depicts the Flash of two Worlds. The Flash from Earth-1 and Earth-2. Behind them there is a line-art graphic of four Earths, overlapping each other as if to suggest the multi-vibrational nature of the many Earths. This graphic treatment would become the logo for COIE. Perhaps there’s an earlier version of this graphical treatment? Maybe my readers know? Still, it is an interesting artifact that predates COIE by 8 years.

No Prize

DC & Marvel encouraged the fandom to make these kinds of investigations. The letters pages in most comic books were a hotbed of reader discussions on the many narrative ‘complexities’ haunting both universes. Marvel made this into a virtue, by instituting the No Prize. Marvel editors awarded a No Prize to readers who came up with the best explanations for odd inconsistencies found in their stories. In effect, the letters pages blended with the fictional worlds, and some of the explanations could, and maybe should be considered canon.

Prophecy

In an interesting aside, Gruenwald quotes Paul Levitz article from Amazing Worlds of DC Comics #12 (August 1976 p.8):

“The pivotal time will be October 1986… and in that month, the future of the world will be decided. Either the path of the Great Disaster will be taken, and civilization will fall, or the path of sanity will prevail and the Legion of Super-Heroes will emerge triumphant a thousand years later…”

COIE series ended in April 1986. Did Paul Levitz miss the mark in his prophecy? Did DC miss an opportunity to build on this metafictional prediction? However, if we consider the omniversal nature of comic book fiction, we should turn to another event that happened in October 1986: Marvel launched the New Universe… The New Universe was a new fictional superhero universe that was exactly like our real-world until the ‘White Event’. The White Event was a point of divergence; a diversifal, in the parlance of omniversal theory. The White Event is the moment when the New Universe, began to diverge from ours, and superheroes become possible… One of the main architects behind the new Marvel initiative was Mark Gruenwald… ‘nuff said.

The premise and execution of Omniverse were a bit bonkers, but they also pointed to a way of looking at comics beyond simple, fannish enjoyment. Omniverse should be seen as an interesting and important moment in the development of comics criticism, which at that time was undergoing a renaissance.

Explore more posts related to my Event Horizon column about the comics from 1985-87.