The upcoming Crisis on Infinite Earths (COIE) article that will appear in my TCJ column ended up with a lot of extra material that didn’t make the cut. In the process of writing the article, I generated many concepts and ideas, and thousands of words that don’t quite fit the article. A lot of this stuff is interesting on its own and deserves to be aired. I plan on following up on these ideas in the future. I already posted about Atari Force, the odd precursor to COIE. And a few days ago I wrote about George Perez’s maximalist aesthetic.

Infinite Hyperobjects

One of the first frameworks I tried to use to think about COIE was the concept of hyperobject developed by philosopher Timothy Morton. The massive size of the narrative DC Universe (and the Marvel Universe (MU), which cannot be left out of the discussion) and its enormous influence and its emanations into general culture (via film, TV, toys, games, etc.) seemed tailor made for a concept like hyperobject.

In The Ecological Thought, Morton developed the concept of hyperobjects to describe objects that are so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend spatiotemporal specificity, such as global warming, styrofoam, and radioactive plutonium.[3]

COIE was a massive event that grappled with the metaphysics of the even more massive DCU. The title alone evokes parallels to global warming. A planetary crisis but multiplied infinitely. Maybe looking at DCU through the lens of hyperobjects could be useful.

What is a Hyperobject?

Timothy Morton enumerates five characteristics of hyperobjects:

- Viscous: Hyperobjects adhere to any other object they touch, no matter how hard an object tries to resist. In this way, hyperobjects overrule ironic distance, meaning that the more an object tries to resist a hyperobject, the more glued to the hyperobject it becomes.[29]

- Molten: Hyperobjects are so massive that they refute the idea that spacetime is fixed, concrete, and consistent.[30]

- Nonlocal: Hyperobjects are massively distributed in time and space to the extent that their totality cannot be realized in any particular local manifestation. For example, global warming is a hyperobject that impacts meteorological conditions, such as tornado formation. According to Morton, though, objects don’t feel global warming, but instead, experience tornadoes as they cause damage in specific places. Thus, nonlocality describes the manner in which a hyperobject becomes more substantial than the local manifestations they produce.

- Phased: Hyperobjects occupy a higher-dimensional space than other entities can normally perceive. Thus, hyperobjects appear to come and go in three-dimensional space but would appear differently if an observer could have a higher multidimensional view.[32]

- Interobjective: Hyperobjects are formed by relations between more than one object. Consequently, objects are only able to perceive to the imprint, or “footprint,” of a hyperobject upon other objects, revealed as information. For example, global warming is formed by interactions between the Sun, fossil fuels, and carbon dioxide, among other objects. Yet, global warming is made apparent through emissions levels, temperature changes, and ocean levels, making it seem as if global warming is a product of scientific models, rather than an object that predated its own measurement. – from Wikipedia

Let’s see if the Marvel or DC universe fit into Morton’s definition.

Viscosity

DC & Marvel have viscosity. Object stick to the DC / Marvel universe hyperobjects. For example, both companies have absorbed other companies and their respective ‘universes.’ No matter how long they try to ‘keep them separated,’ inevitably Charlton heroes, New Universe heroes, Fawcett heroes, etc. end up getting sucked into the voracious universes. Even more interestingly, in the ’70s and ’80s, there was a series of official and unofficial crossovers between these two universes. That means, that technically Superman exists in the same fictional universe as Spider-Man. Given enough time, it’s possible to imagine a massive media conglomerate owning both universes, and bringing them together into one super-massive multiverse. Disney’s plan for 2050?

Another way DCU and MU demonstrate viscosity is in their effects on readers. The two universes are ever-expanding and sticky virtual worlds that can be inhabited by the fans to a disturbing degree.

Molten Lava

Both universes operate on a multidimensional level and consistently break and violate the contiguity of their fictional spacetime continuums. This may or may not be by design. But, the continual inconsistencies that creep into the universes need constant vigilance, reboots, etc. A good example of that is Ed Piskor’s X-Men Grand Design. Piskor sutures decades of X-Men continuity — originally written and drawn by many different contributors — as if it was a single-story all along. The comic retelling functions like a history book, creating a unified narrative out of disparate historical events.

Both universes have lasted for decades and have produced an enormous amount of artifacts.

Nonlocality

Within their internal narrative logic, both universes are massively distributed in space and time. Both universes encompass universes (multi-verses even) and timelines stretch billions of years into the past and present. Reading a single Marvel or DC title never gets you even close to the totality of those universes. Beyond internal nonlocality, it is also nonlocal in the real world. The characters and concepts have spilled out into other media, books, TV, Film. Most recently Marvel Studios succeeded (before DC again) in porting the shared universe into film.

Picking up a single DCU or MU artifact, a neophyte is aware of a larger context, but the enormity of it eludes even the hardcore fans.

Phased

Both universes are phased and higher dimensional. They have this quality in both, their physical manifestation (as comic book made of paper) and in the fictional universe that emerges from their pages. We lack the perceptual apparatus to comprehend them in totality. We can only experience it one comic book, one TV show, or film at a time.

Additionally, we are largely unaware of the hidden forces behind the scenes, corporate decision, editorial mandates, moods of writers and artists, etc. all of which have effects on the universe we actually see.

Interobjective

This is maybe the clearest parallel. Each comic book, TV show, film, etc. is a footprint of something larger. Each one contains breadcrumbs in the narrative that can lead us to other corners. Crossover titles deliberately intensify narratives to reveal more of the universe. Seeing Wolverine appear in a Spider-Man title gives us a small glimpse of the massive X-Men comics continuity. Which itself is largely invisible, though interwoven with, the continuity of the Avengers, or The Punisher.

How to Manage a Universe?

COIE is perhaps the only comic book that attempted to map and manage a hyperobject as vast as the DCU. In fact, paradoxically, it’s an attempt to manage… to de-hyperobject the DCU at the narrative level… in order to expand the hyperobject on the commercial and cultural level.

If you’re someone interested in comics as a medium either as a reader, or as a professional, the DCU and MU, were something that would confront you whether you wanted it or not. You may consciously avoid it, or just have no interest in it, but almost any conversation around comics would have to contend with DCU or MU. These two behemoths nearly consumed comics as a medium.

Infinite Terror

“Hyperobjects invoke a terror beyond the sublime… A massive cathedral dome, the mystery of a stone circle, have nothing on the sheer existence of hyperobjects.” Morton’s description evokes Lovecraftian cthuloid entities.

In an interview, Dan Clowes (Eightball, Ghost World, David Boring), recounted many moments of mounting horror when a stranger on an airplane asks him what he does. Once he’d answer that he made comic books, inevitably the immediate follow-up questions would be, “Which superhero do you draw?”

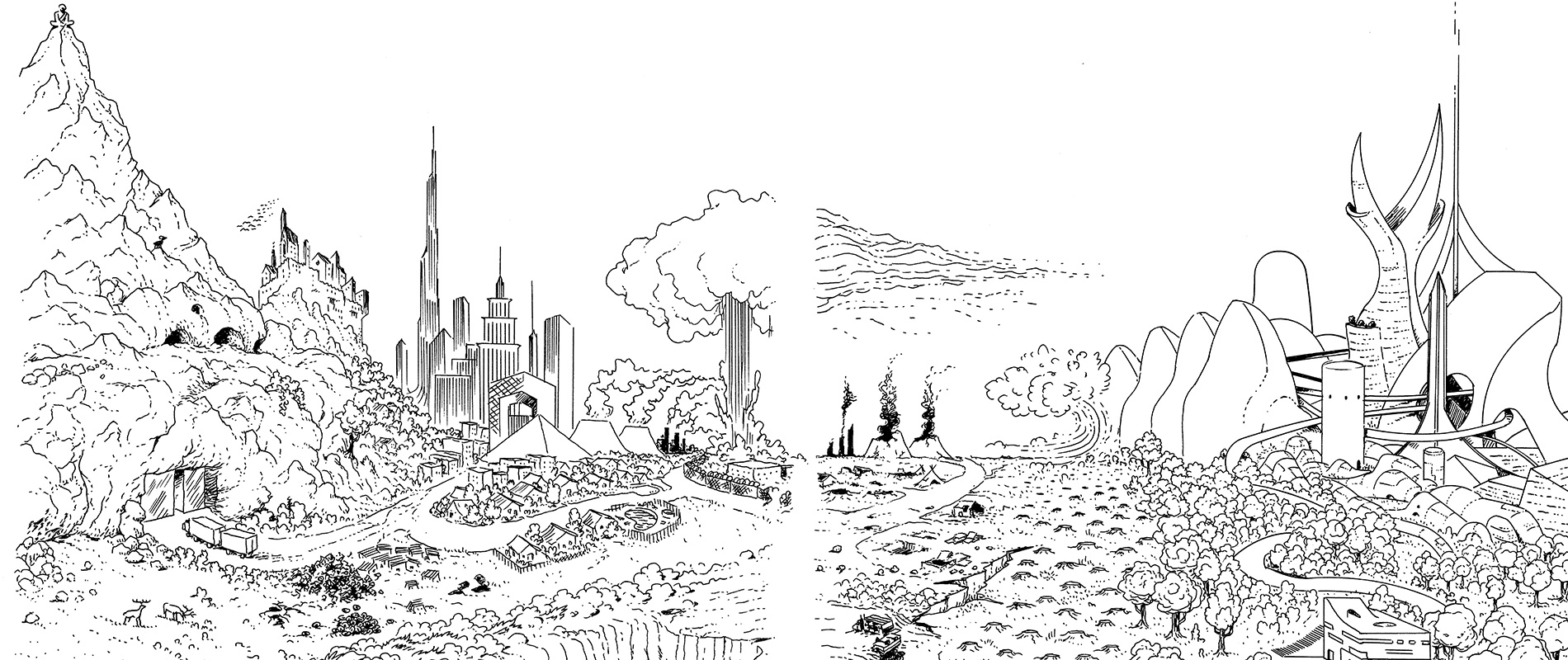

Ultimately, I’m not sure if DCU or MU qualify as hyperobjects, though they share some qualities. They may however be emanations of a much more vast hyperobject… the massive industrial-entertainment complex that generates hyper-immersive fictional narratives inhabited by billions on this planet. It consumes massive resources and functions as an ideological safety valve for capital. These infinite worlds are multiplying rapidly around us as we hurtle through the yawning cold universe to our ultimate final crisis.

Explore more posts related to my Event Horizon column about the comics from 1985-87.

0 Replies to “Infinite Hyperobjects: Crisis on Infinite Earths”